Step 2: Design

Chapter 4 - What do the countries’ KAP scores tell us?

Note: This chapter looks at the Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) score results across the different countries. The results of the individual KAP score questions is also examined and provides more detailed insights into where specific knowledge, attitude and practice gaps can be found, and feeds into message development for the planned country campaigns.

KEY MESSAGES

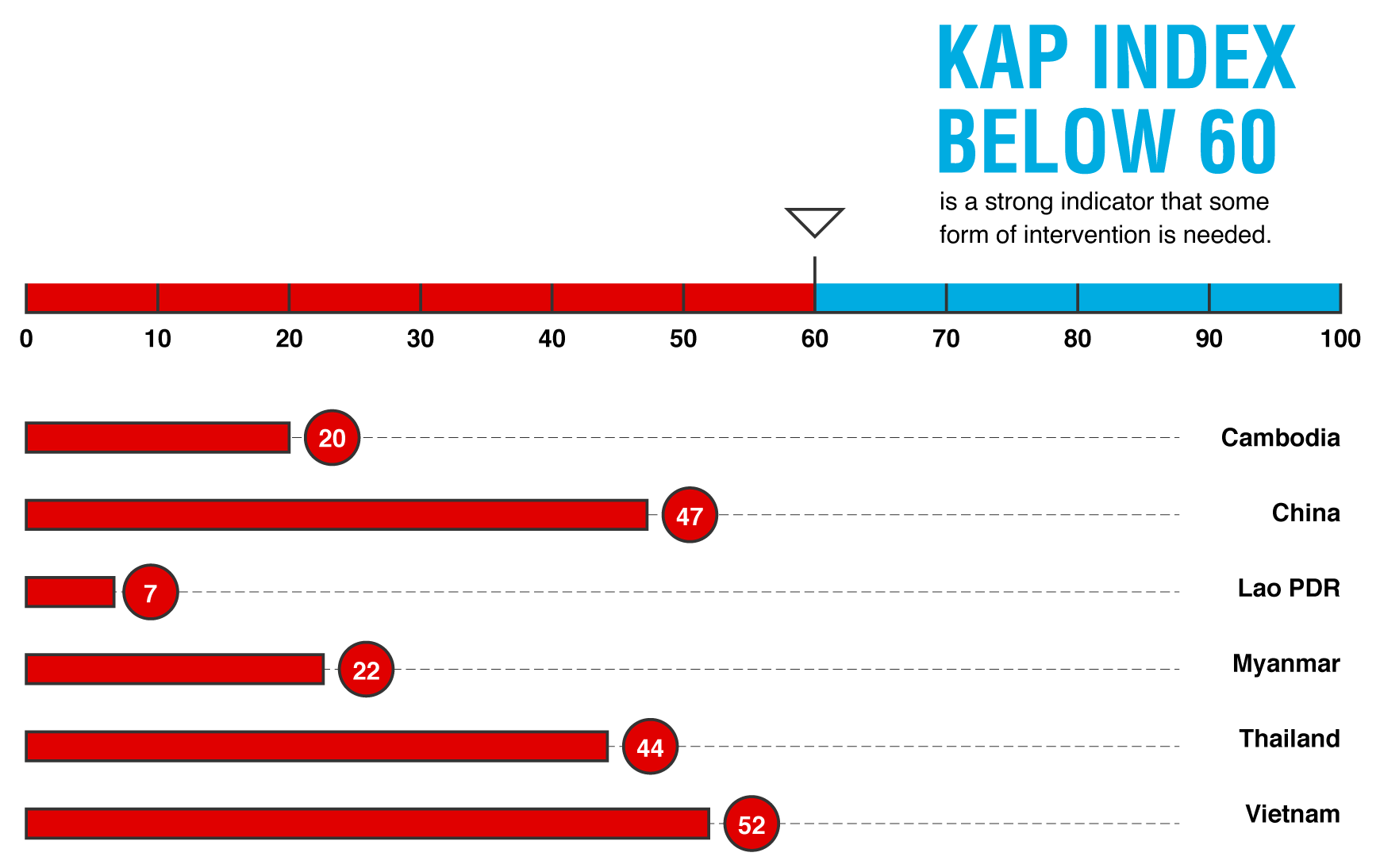

The results from the KAP analysis shows that people have different levels of knowledge, hold different attitudes and do not behave in the same ways. The KAP scores show higher levels of knowledge in Vietnam (73), followed by Thailand (56) and China (47), indicating that these countries are ready to transition from knowledge to action. Meanwhile, KAP scores are relatively low in Lao PDR (7), Cambodia (19) and Myanmar (22), indicating that these countries are still in the ‘knowledge formation’ stage.

Social norms are more pronounced in rural areas when looking at Cambodia and Thailand. However, the opposite is true for Lao PDR and Myanmar. The results show that social norms influence people to some extent concerning forest crime and in buying hardwood furniture.

The common thread across all countries is lack of knowledge regarding how consumer demand drives illegal logging, attitudes dominated by apathy (do not care about illegal logging), and not being willing to report a forest crime or supporting forest protection activities.

All countries surveyed have KAP scores lower than 60 indicating that some form of intervention is needed.

4.1. KAP index is higher in countries with higher incomes and urban areas

The KAP Index is a one-number indicator in which the answers to the knowledge, attitudinal and behavioural questions have been aggregated. A high KAP Index is synonymous with high behavioural compliance, meaning people are more likely to take actions that would mitigate the impact of forest crime, such as not buying hardwood from endangered species or engaging in illegal logging activities.

Higher educational attainment, access to information and socio-economic status are likely playing a positive influence on the KAP scores of people in urban areas. The survey found that all countries except Lao PDR had higher KAP index in urban areas compared to rural areas, indicating that people in urban areas have a better understanding of illegal logging and its impact.

4.2. A significant proportion of people are in the lower stages of change

The KAP segmentation indicator shows how the respondents are distributed across the stages of change.

Knowing where most respondents are along the stages of change determines the type of campaign needed.

On the other hand, in China, Thailand, and Vietnam, more respondents were found at the higher stages of change (attitude, intention and compliance). While these countries also have significant numbers of people for which further education is needed, around one in every five or six people are aware of the issues regarding forest crime and are willing to take action. This indicates that people are somewhat polarised, which is evident when looking at the KAP Segmentation in Vietnam. Hence, in these countries, there is an opportunity for campaigns to engage with people who already have a favourable mindset to influence others.

Knowledge Formation

Belief

Attitude

Intention

Compliance

The higher the KAP score is, the higher the behavioural compliance could be. But the vast majority of respondents were in the first three stages of change.

4.3. Social norms can influence KAP scores

When looking at behaviour change, it is essential to consider the potential impact of social norms. Strong social norms can influence people to behave against their conscience or what they believe is right. In such cases, affecting people to change their behaviour may be less effective unless social norms are also tackled.

The results show that social norms influence people to some extent concerning forest crime and buying hardwood. Social norms must certainly be considered in countries like Cambodia and Lao PDR and to some extent in other countries. Engaging with opinion leaders in Thailand and Vietnam to influence others could be a good campaign strategy.

4.4. People lack knowledge on the link between consumer demand and illegal logging

Respondents in the Lower Mekong countries have a relatively good understanding regarding the occurrence of illegal logging in their countries, and that deforestation is a major driver of climate change. There is also relatively good understanding about how illegal logging impacts the environment.

4.5. Attitudes towards illegal logging vary by country

People express apathy towards illegal logging and think the problem is exaggerated. Moreover, they do not feel illegal logging is a problem that can be solved and there is a perception that buying furniture from protected tree species is more important the impacts of illegal logging. This result is consistent with the higher level of demand for hardwood furniture in China.

All in all, a positive attitude is a good indicator for a campaign if it seeks to engage with people. When attitudes are generally positive, engagement will be relatively easier since people can relate to the problem and many would be willing to do something about it. The high levels of apathy represents a challenge and means involvement must come with a clear purpose. Hence, engagement can be a strategy for some countries and was considered when formulating the recommendations.

4.6. Behavioural compliance is high in China but low in Cambodia and Lao PDR

China stands out as the country with the highest level of compliance

In contrast, respondents from Myanmar, Cambodia, and Lao PDR shows lower levels of compliance in both urban and rural areas.

Not buying certified products can be explained by the relatively low demand for hardwood. However, while attitudes showed that people were against illegal logging activities, the negative effects of such activities are not something people talk about, nor is there an indication that people have supported forest protection activities. This could potentially be explained by a lack of opportunity to do so.

Conclusion

The results from the KAP analysis show that urban and rural respondents in each country have different levels of knowledge, hold different attitudes and do not behave in the same ways.

However, there is an overarching concept that can explain some of these differences and that people are at different development stages when it come to how well they understand the link between demand for hardwood and the impact of illegal logging.

The KAP analysis shows that conventional thinking is linear; illegal logging can lead to climate change. Because of the attention given to illegal logging in the media and the ongoing debate about climate change, it is easy to see how these issues are at top of mind of many people. But this simplified view of the problem takes the consumer out of the equation, putting them on the sideline as a spectator rather than as a participant. The common thread across all countries is lack of knowledge regarding how consumer demand drives illegal logging, attitudes dominated by apathy (do not care about illegal logging), and not being willing to report a forest crime or supporting forest protection activities. Strengthening awareness of the links between consumer demand and forest crime is key, and when possible, engaging with people who can be regarded as opinion leaders to influence others. It is important to recognise that most of the respondents in this study are not consumers of hardwood. It is therefore essential to translate the findings into interventions that are tailored for each country. In urban communities, the promotion of certification systems and social marketing campaigns could be used in an attempt to lessen the demand for illegal logging. In rural communities, better law enforcement and community reporting could be a solution. For the different country campaigns these results will be helpful, both in terms of understanding message development and how to formulate appropriate calls to action. The next chapter explores media usage trends across the Lower Mekong region, and examines potential channels for engaging local people with content related to forest crime.